The stranger in the chat box is terrified they’re going to hurt themselves.

The young adult recently lost their job. They’ve been depressed and have an idea how they will end their life.

They even have a date in mind.

Tomorrow.

“I just need to talk to someone,” they plead with New Jersey’s 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. “Please.”

Jesse Szwed, 25, silently reads the messages on his laptop, his blue eyes intensely focused on the screen. He hunches forward and begins typing.

Three hours ago, he was doing his laundry. Now Szwed is trying to save a life.

The trained crisis counselor doesn’t know anything about the person in the online chat except what they’ve shared. The desperate visitor knows nothing at all about him.

Chance has brought the two New Jerseyans together. What happens next could be the difference between life and death.

“I’m here for you,” writes Szwed, a recent College of New Jersey graduate with black-framed glasses and a fashionably scruffy, brown beard. “We can speak as long as you need.”

Szwed works for 988′s text and chat service, where each shift is a journey into the unknown, a treacherous high-wire act with tragedy lurking at every turn. NJ Advance Media shadowed him over two spring nights, revealing a rare window into the evolving front lines of an alarming public health emergency.

Teenage girls are spiraling in unprecedented levels of hopelessness. Older adults are suffering from extreme loneliness. And the national suicide rate rose 4% in 2021 after two years of decline, all part of what U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has declared the mental health “crisis of our times.”

The nationwide 988 program debuted last year and is reporting record demand after replacing an old 1-800 number.

The text and chat service alone responds to 122,000 contacts a month on average, a symptom of a mental health system never designed to handle a crisis so severe. In the pit of their most dire moments, struggling people of all ages reach out anonymously to be helped, heard or consoled.

“You see that little bubble that says they’re typing, and you’re just waiting, thinking, ‘OK, how bad is it going to be?’” said Szwed, part of the New Jersey 988 team responding to residents from 6-10 on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights.

“These conversations could be the last time this person ever interacts with someone,” said Tony Ciavolella, program director for New Jersey 988 Chat & Text and assistant executive director for CONTACT of Mercer County, the nonprofit whose staff of 11 counselors operates the 988 line with state funding. “So the interactions have to be taken with the utmost importance, respect and compassion.”

Text and chat options make 988 more anonymous and accessible, especially for young people in crisis. But technology has made painful conversations more challenging.

Szwed can’t use his calming voice to soothe a distraught caller or interpret their tone to gauge their state of mind like counselors on 988′s phone line.

Instead, he reads the young adult’s startling response, and he types.

Then he waits.

He knows a life might be on the line.

A week earlier, a chat from a distressed student popped up on Szwed’s screen.

“I need to talk about problems,” they write near the beginning of Szwed’s four-hour shift.

Crisis lines are mental health triage. Take the call. Assess the risk. Get them through the night with a plan for tomorrow. The vast majority of chats won’t end in tragedy. But the underlying problems aren’t getting resolved.

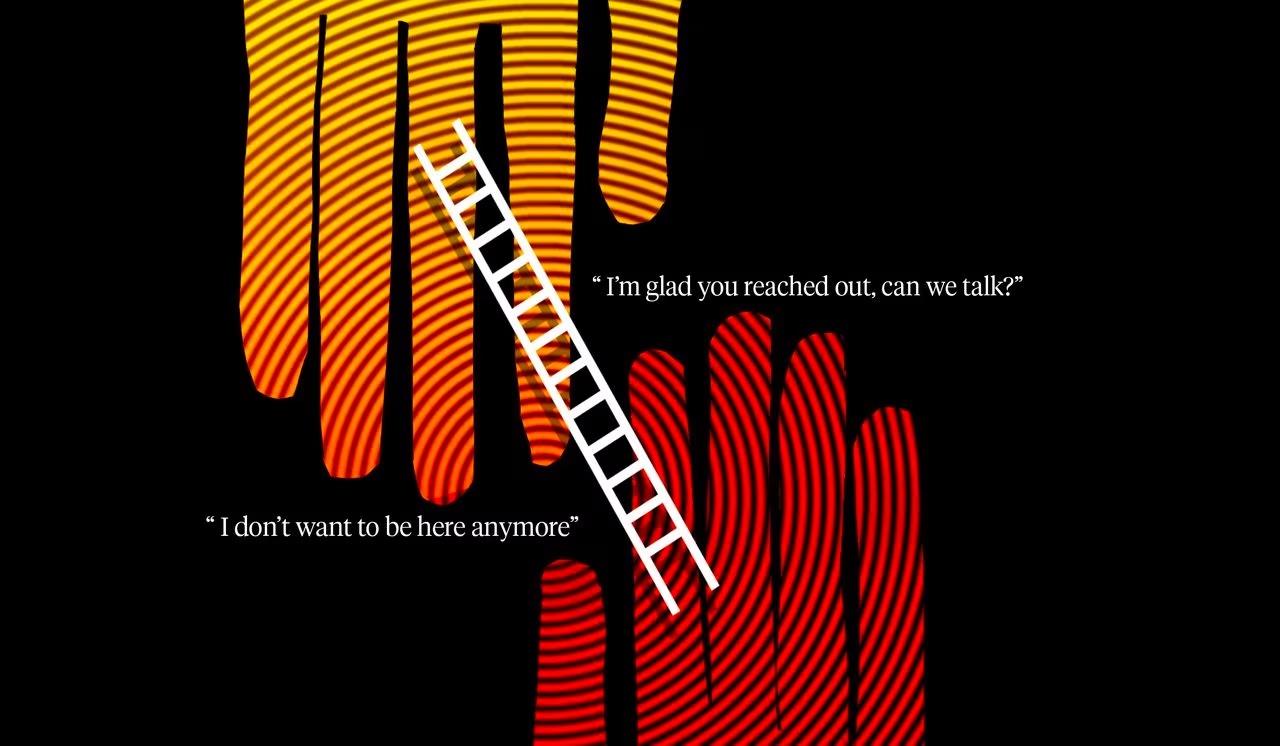

“You’ll have a youth text you, ‘I’m thinking about killing myself,’ and you’re like, ‘I’m glad you reached out. Can we talk?’” said Bart Andrews, chief clinical officer of a St. Louis-based helpline and a leading expert on suicide crisis lines. “You won’t get a response for like five minutes. It’s incredibly, incredibly scary.”

A typical night doesn’t exist in suicide prevention, Szwed said. Chats can last a few seconds or a few hours. Some people just want to talk. Others have a gun and a plan.

The student with problems falls in between, it would seem.

“I am more than happy to listen,” Szwed writes back, using only his two index fingers in a hybrid hunt and peck. “What would you want to talk about?”

The student unloads.

Depression. Family. Friends. School. Work. It all feels like it’s piling up.

“I don’t want to be here anymore,” they write.

Suicide is still rare, especially in New Jersey, which has the lowest rate in the country. But Szwed knew three people in his social orbit who have died by suicide since he was 13. That’s not counting a 15-year-old who killed herself at his high school, Hunterdon Central Regional, just six months after he graduated in 2017.

“Depression can take a heavy toll,” Szwed responds to the student. “It sounds like that might be a part of how we got to this point.”

Nobody talked about mental health when Szwed was growing up in Delaware Township. He didn’t think about depression or anxiety until he saw friends and classmates struggling with PTSD and self-harm and decided he wanted to help.

His first crisis line shift was a baptism by fire: a suicidal caller on the 988 phone line.

He’s still haunted by the conviction in their voice last fall when they said they wouldn’t live to see another day. His heart pounded. His entire body shook. Then instincts took over. He told the caller he cared about them and they mattered to him even if they were just strangers on the phone.

The caller gradually calmed down and agreed to seek counseling.

“It’s one of those jobs where there is no other way to do it than to go into the deep end,” Szwed said from CONTACT of Mercer County’s office in Pennington, where he sits alone at a small folding table with two windows behind him. He’s brought his Dell laptop tagged with a Pink Floyd sticker, a white legal pad and a manilla folder stuffed full of mental health resources in all 21 counties.

The intensity of training alone sometimes scares away prospective counselors, said Dawn Tringali, a 988 counselor and training manager for CONTACT. It’s 10 weeks of role-play scenarios, instructional videos, and mastering active listening techniques and strategies for asking difficult questions with empathy.

“Somebody texted me at two o’clock in the morning and said, ‘I still can’t sleep from a role-play scenario we had. It triggered me, and I can’t go on,’” said Tringali, who became a crisis counselor after her father died by suicide two days after his 70th birthday.

Szwed, an avid swing dancer in his free time, graduated from TCNJ in May with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. He plans to earn a master’s degree in social work.

Someday he might be a school counselor. First, he has to pose the question that must be broached in every chat.

“You mentioned not wanting to be here anymore. May I ask, are you referring to suicide when you say that?” he writes to the student.

The response is vague. The student says they are insecure and no one cares about them.

Szwed asks again if they are thinking of killing themselves.

“I want to,” the student says, “but I am so afraid to.”

Listening and validating is the first phase of crisis response. Then comes risk assessment.

The difference between suicidal ideation and a suicide plan is critical. Someone who thinks about maybe jumping off a bridge has ideation. Someone who has driven to a specific bridge and intends to jump tonight because their mother died at the same spot exactly 10 years ago has a plan.

An imminent crisis escalates the stakes and, in extreme cases, can trigger a call to emergency responders.

“The first three years that I’ve done this, I could count on one hand how many times we needed police rescue,” Tringali said. “And in the past year and a half, I can tell you that we call for rescue maybe three to five times in a week.”

Szwed is trying to make sure it won’t come to that tonight.

“Have you made some sort of plan about how you would go about that?” he asks the student.

They haven’t.

The chat stretches on for about 25 minutes. Szwed convinces the student to focus on their future aspirations, a positive reason to live.

Soon the messages stop coming.

“I just need someone to talk to,” a dejected 988 user says over text message, which appears in a box on Szwed’s screen.

The texter unleashes a flurry of messages coming in five or six at a time.

Szwed leans back and reads carefully.

“We were doing so well. We spoke every day,” the person texts about their boyfriend.

The couple had talked about getting married and someday having children.

“Then he got distant,” they say.

Szwed is an active listener and exceptional communicator with an analytical mind, Ciavolella said, making him one of New Jersey 988′s best counselors.

Text and chat is informal by nature, but Szwed tries to respond as professionally as possible. He never uses emojis, exclamation points or all-caps. He frequently deletes what he’s written and starts over, scrutinizing every word.

But he responds to this texter quickly, hoping to rule out suicide.

And praying the right sentiment gets through.

“Sometimes when relationships can get difficult, some people can begin to have thoughts of suicide,” Szwed writes. “Is that something that might be happening for you now?”

“No,” the texter replies.

Only about 10% of calls and chats will involve suicide, said Katherine Delgado, a veteran of the crisis lines and now senior director of programs for the American Association of Suicidology.

The rest run “a gamut of issues,” including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, concern about relatives and people who just need to talk, she said.

Regardless of the topic, every call or chat on a crisis line must be taken seriously, according to Szwed.

“Young people’s mental health is in danger,” he said. “I don’t think young people fully understand that those resources are available to them on the magnitude that they need right now.”

The texter breezes past the suicide question and continues delving into their relationship issues.

Another blitz of messages pops up on Szwed’s screen.

The unanswered message still haunts Tringali.

The CONTACT training manager had just finished a chat a few years ago on another crisis line and saw a message from an 11-year-old boy who had been waiting.

“Hello. Hello. Hello. Please answer. I just need someone to tell me it’s OK,” the boy wrote.

He left the chat before anyone could respond.

“Think about how desperate he had to be that he couldn’t turn to his family,” Tringali said.

Horror stories such as that are why New Jersey’s line is connected to overflow centers in other states when volume spikes, Ciavolella said.

Early crisis lines popped up in the 1960s and were understaffed and underfunded. Hundreds of grassroots lines launched by nonprofits, volunteers and religious groups often struggled to handle the call volume with no way to transfer backlogged callers from one line to another.

These days, if a counselor is waiting for more than a few minutes between chats, the crisis line knows it is adequately staffed, said Andrews, the expert from the St. Louis area.

And so it was for Szwed on a recent warm night.

The low hum of a fan was the only sound in the room. He was between chats as the sun set behind him.

At his busiest, he’s talked with as many as seven different people in a night. On his slowest shift, he once waited four hours without a single crisis.

Crisis lines typically see an influx of callers around the holidays. They also receive a surge of calls in May and June, the peak of wedding and graduation season.

In May, the national text and chat line handled more than 139,000 contacts, the most in a month since 988 launched in July 2022. Call volume usually ranges between 220,000 and 250,000 a month.

But if people are reaching out, there’s a chance to help them.

“When someone knows that they have this option, they’re not out of options,” Szwed said. “And that means they are not out of hope.”

Thirty minutes tick by on a small clock on the white cinder block wall beside him. He cracks his knuckles and sips fountain Diet Coke from a paper cup.

He’s learned to live in the silence.

After nearly an hour, Szwed’s computer finally rings with a chime-like tone. He types a welcome message and waits.

The person quickly leaves without saying a word.

Szwed shakes his head from side to side with concern.

The suicidal young adult he’s been talking with says they’ve been drinking.

The young adult then makes a startling admission: They’ve been cutting as they chat.

Szwed takes a deep breath and again starts to type.

“I’d like to ask, because you mentioned that you’re cutting yourself now, do you think you need medical attention?” he writes.

He drums his fingers on the corner of his computer and waits.

If the crisis line were a dance, the visitor would be the lead, he says. But counselors sometimes need to assert control without pushing too hard.

Szwed waits for a response and nervously chomps on peppermint gum.

“I just need to talk to someone,” the young adult says.

The back and forth continues, but the messages become so riddled with typos that Szwed can’t make sense of them.

In 30 minutes, they exchange about 60 messages. Yet they haven’t moved from risk assessment to the final phase of a chat: safety planning. What steps can be taken moving forward to help?

Szwed’s cheeks and forehead turn red.

He’s worried.

It’s hotter this week than last, and a window air conditioning unit rumbles in the background as he quietly waits for another response.

“No!” Szwed abruptly shouts.

The person has ended the chat.

Szwed slumps his shoulders after the suicidal young adult leaves.

His voice drops.

“Of course, you’re going to wonder,” he says. “They never said bye or anything like that, so I don’t know what happened.”

Szwed has interacted with hundreds of people on the 988 lines since he started last fall.

Some thank him before disconnecting or even say he’s saved their life. But ambiguous endings are common. People open up. He listens. Then they leave.

He never knows how their stories end.

What happens tomorrow? Or next week? Or next month? The rest of their lives are a mystery.

Szwed tries to accept that he’s done everything he can and move forward. But it’s not always easy.

“It will eat at you if you let it,” he says.

It’s just one more night in a long and difficult journey.

He begins writing his post-chat report, a requirement for every interaction regardless of the length of the chat or its circumstances.

Taken together, the faceless, confidential documents chronicle the intimate details of a mental health crisis that has devastated families, overwhelmed the health care system and pushed countless New Jerseyans to the brink. He writes of people’s deepest secrets and lowest moments.

So many are going through the same experiences, he said. He wishes they didn’t feel shame.

“It’s shocking how many people are still just not sharing it with anyone,” he said. “The number of times I’ve been the first person someone shared a horrible, horrifying experience with is just unfair.”

He files the report and silently waits for the next crisis. The air conditioning hums in the background.

A few minutes later, he hears the chime again.

The stranger in the chat box is terrified they’re going to hurt themselves.

The young adult recently lost their job. They’ve been depressed and have an idea how they will end their life.

They even have a date in mind.

Tomorrow.

“I just need to talk to someone,” they plead with New Jersey’s 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. “Please.”

Jesse Szwed, 25, silently reads the messages on his laptop, his blue eyes intensely focused on the screen. He hunches forward and begins typing.

Three hours ago, he was doing his laundry. Now Szwed is trying to save a life.

The trained crisis counselor doesn’t know anything about the person in the online chat except what they’ve shared. The desperate visitor knows nothing at all about him.

Chance has brought the two New Jerseyans together. What happens next could be the difference between life and death.

“I’m here for you,” writes Szwed, a recent College of New Jersey graduate with black-framed glasses and a fashionably scruffy, brown beard. “We can speak as long as you need.”

Szwed works for 988′s text and chat service, where each shift is a journey into the unknown, a treacherous high-wire act with tragedy lurking at every turn. NJ Advance Media shadowed him over two spring nights, revealing a rare window into the evolving front lines of an alarming public health emergency.

Teenage girls are spiraling in unprecedented levels of hopelessness. Older adults are suffering from extreme loneliness. And the national suicide rate rose 4% in 2021 after two years of decline, all part of what U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has declared the mental health “crisis of our times.”

The nationwide 988 program debuted last year and is reporting record demand after replacing an old 1-800 number.

The text and chat service alone responds to 122,000 contacts a month on average, a symptom of a mental health system never designed to handle a crisis so severe. In the pit of their most dire moments, struggling people of all ages reach out anonymously to be helped, heard or consoled.

“You see that little bubble that says they’re typing, and you’re just waiting, thinking, ‘OK, how bad is it going to be?’” said Szwed, part of the New Jersey 988 team responding to residents from 6-10 on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights.

“These conversations could be the last time this person ever interacts with someone,” said Tony Ciavolella, program director for New Jersey 988 Chat & Text and assistant executive director for CONTACT of Mercer County, the nonprofit whose staff of 11 counselors operates the 988 line with state funding. “So the interactions have to be taken with the utmost importance, respect and compassion.”

Text and chat options make 988 more anonymous and accessible, especially for young people in crisis. But technology has made painful conversations more challenging.

Szwed can’t use his calming voice to soothe a distraught caller or interpret their tone to gauge their state of mind like counselors on 988′s phone line.

Instead, he reads the young adult’s startling response, and he types.

Then he waits.

He knows a life might be on the line.

A week earlier, a chat from a distressed student popped up on Szwed’s screen.

“I need to talk about problems,” they write near the beginning of Szwed’s four-hour shift.

Crisis lines are mental health triage. Take the call. Assess the risk. Get them through the night with a plan for tomorrow. The vast majority of chats won’t end in tragedy. But the underlying problems aren’t getting resolved.

“You’ll have a youth text you, ‘I’m thinking about killing myself,’ and you’re like, ‘I’m glad you reached out. Can we talk?’” said Bart Andrews, chief clinical officer of a St. Louis-based helpline and a leading expert on suicide crisis lines. “You won’t get a response for like five minutes. It’s incredibly, incredibly scary.”

A typical night doesn’t exist in suicide prevention, Szwed said. Chats can last a few seconds or a few hours. Some people just want to talk. Others have a gun and a plan.

The student with problems falls in between, it would seem.

“I am more than happy to listen,” Szwed writes back, using only his two index fingers in a hybrid hunt and peck. “What would you want to talk about?”

The student unloads.

Depression. Family. Friends. School. Work. It all feels like it’s piling up.

“I don’t want to be here anymore,” they write.

Suicide is still rare, especially in New Jersey, which has the lowest rate in the country. But Szwed knew three people in his social orbit who have died by suicide since he was 13. That’s not counting a 15-year-old who killed herself at his high school, Hunterdon Central Regional, just six months after he graduated in 2017.

“Depression can take a heavy toll,” Szwed responds to the student. “It sounds like that might be a part of how we got to this point.”

Nobody talked about mental health when Szwed was growing up in Delaware Township. He didn’t think about depression or anxiety until he saw friends and classmates struggling with PTSD and self-harm and decided he wanted to help.

His first crisis line shift was a baptism by fire: a suicidal caller on the 988 phone line.

He’s still haunted by the conviction in their voice last fall when they said they wouldn’t live to see another day. His heart pounded. His entire body shook. Then instincts took over. He told the caller he cared about them and they mattered to him even if they were just strangers on the phone.

The caller gradually calmed down and agreed to seek counseling.

“It’s one of those jobs where there is no other way to do it than to go into the deep end,” Szwed said from CONTACT of Mercer County’s office in Pennington, where he sits alone at a small folding table with two windows behind him. He’s brought his Dell laptop tagged with a Pink Floyd sticker, a white legal pad and a manilla folder stuffed full of mental health resources in all 21 counties.

The intensity of training alone sometimes scares away prospective counselors, said Dawn Tringali, a 988 counselor and training manager for CONTACT. It’s 10 weeks of role-play scenarios, instructional videos, and mastering active listening techniques and strategies for asking difficult questions with empathy.

“Somebody texted me at two o’clock in the morning and said, ‘I still can’t sleep from a role-play scenario we had. It triggered me, and I can’t go on,’” said Tringali, who became a crisis counselor after her father died by suicide two days after his 70th birthday.

Szwed, an avid swing dancer in his free time, graduated from TCNJ in May with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. He plans to earn a master’s degree in social work.

Someday he might be a school counselor. First, he has to pose the question that must be broached in every chat.

“You mentioned not wanting to be here anymore. May I ask, are you referring to suicide when you say that?” he writes to the student.

The response is vague. The student says they are insecure and no one cares about them.

Szwed asks again if they are thinking of killing themselves.

“I want to,” the student says, “but I am so afraid to.”

Listening and validating is the first phase of crisis response. Then comes risk assessment.

The difference between suicidal ideation and a suicide plan is critical. Someone who thinks about maybe jumping off a bridge has ideation. Someone who has driven to a specific bridge and intends to jump tonight because their mother died at the same spot exactly 10 years ago has a plan.

An imminent crisis escalates the stakes and, in extreme cases, can trigger a call to emergency responders.

“The first three years that I’ve done this, I could count on one hand how many times we needed police rescue,” Tringali said. “And in the past year and a half, I can tell you that we call for rescue maybe three to five times in a week.”

Szwed is trying to make sure it won’t come to that tonight.

“Have you made some sort of plan about how you would go about that?” he asks the student.

They haven’t.

The chat stretches on for about 25 minutes. Szwed convinces the student to focus on their future aspirations, a positive reason to live.

Soon the messages stop coming.

“I just need someone to talk to,” a dejected 988 user says over text message, which appears in a box on Szwed’s screen.

The texter unleashes a flurry of messages coming in five or six at a time.

Szwed leans back and reads carefully.

“We were doing so well. We spoke every day,” the person texts about their boyfriend.

The couple had talked about getting married and someday having children.

“Then he got distant,” they say.

Szwed is an active listener and exceptional communicator with an analytical mind, Ciavolella said, making him one of New Jersey 988′s best counselors.

Text and chat is informal by nature, but Szwed tries to respond as professionally as possible. He never uses emojis, exclamation points or all-caps. He frequently deletes what he’s written and starts over, scrutinizing every word.

But he responds to this texter quickly, hoping to rule out suicide.

And praying the right sentiment gets through.

“Sometimes when relationships can get difficult, some people can begin to have thoughts of suicide,” Szwed writes. “Is that something that might be happening for you now?”

“No,” the texter replies.

Only about 10% of calls and chats will involve suicide, said Katherine Delgado, a veteran of the crisis lines and now senior director of programs for the American Association of Suicidology.

The rest run “a gamut of issues,” including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, concern about relatives and people who just need to talk, she said.

Regardless of the topic, every call or chat on a crisis line must be taken seriously, according to Szwed.

“Young people’s mental health is in danger,” he said. “I don’t think young people fully understand that those resources are available to them on the magnitude that they need right now.”

The texter breezes past the suicide question and continues delving into their relationship issues.

Another blitz of messages pops up on Szwed’s screen.

The unanswered message still haunts Tringali.

The CONTACT training manager had just finished a chat a few years ago on another crisis line and saw a message from an 11-year-old boy who had been waiting.

“Hello. Hello. Hello. Please answer. I just need someone to tell me it’s OK,” the boy wrote.

He left the chat before anyone could respond.

“Think about how desperate he had to be that he couldn’t turn to his family,” Tringali said.

Horror stories such as that are why New Jersey’s line is connected to overflow centers in other states when volume spikes, Ciavolella said.

Early crisis lines popped up in the 1960s and were understaffed and underfunded. Hundreds of grassroots lines launched by nonprofits, volunteers and religious groups often struggled to handle the call volume with no way to transfer backlogged callers from one line to another.

These days, if a counselor is waiting for more than a few minutes between chats, the crisis line knows it is adequately staffed, said Andrews, the expert from the St. Louis area.

And so it was for Szwed on a recent warm night.

The low hum of a fan was the only sound in the room. He was between chats as the sun set behind him.

At his busiest, he’s talked with as many as seven different people in a night. On his slowest shift, he once waited four hours without a single crisis.

Crisis lines typically see an influx of callers around the holidays. They also receive a surge of calls in May and June, the peak of wedding and graduation season.

In May, the national text and chat line handled more than 139,000 contacts, the most in a month since 988 launched in July 2022. Call volume usually ranges between 220,000 and 250,000 a month.

But if people are reaching out, there’s a chance to help them.

“When someone knows that they have this option, they’re not out of options,” Szwed said. “And that means they are not out of hope.”

Thirty minutes tick by on a small clock on the white cinder block wall beside him. He cracks his knuckles and sips fountain Diet Coke from a paper cup.

He’s learned to live in the silence.

After nearly an hour, Szwed’s computer finally rings with a chime-like tone. He types a welcome message and waits.

The person quickly leaves without saying a word.

Szwed shakes his head from side to side with concern.

The suicidal young adult he’s been talking with says they’ve been drinking.

The young adult then makes a startling admission: They’ve been cutting as they chat.

Szwed takes a deep breath and again starts to type.

“I’d like to ask, because you mentioned that you’re cutting yourself now, do you think you need medical attention?” he writes.

He drums his fingers on the corner of his computer and waits.

If the crisis line were a dance, the visitor would be the lead, he says. But counselors sometimes need to assert control without pushing too hard.

Szwed waits for a response and nervously chomps on peppermint gum.

“I just need to talk to someone,” the young adult says.

The back and forth continues, but the messages become so riddled with typos that Szwed can’t make sense of them.

In 30 minutes, they exchange about 60 messages. Yet they haven’t moved from risk assessment to the final phase of a chat: safety planning. What steps can be taken moving forward to help?

Szwed’s cheeks and forehead turn red.

He’s worried.

It’s hotter this week than last, and a window air conditioning unit rumbles in the background as he quietly waits for another response.

“No!” Szwed abruptly shouts.

The person has ended the chat.

Szwed slumps his shoulders after the suicidal young adult leaves.

His voice drops.

“Of course, you’re going to wonder,” he says. “They never said bye or anything like that, so I don’t know what happened.”

Szwed has interacted with hundreds of people on the 988 lines since he started last fall.

Some thank him before disconnecting or even say he’s saved their life. But ambiguous endings are common. People open up. He listens. Then they leave.

He never knows how their stories end.

What happens tomorrow? Or next week? Or next month? The rest of their lives are a mystery.

Szwed tries to accept that he’s done everything he can and move forward. But it’s not always easy.

“It will eat at you if you let it,” he says.

It’s just one more night in a long and difficult journey.

He begins writing his post-chat report, a requirement for every interaction regardless of the length of the chat or its circumstances.

Taken together, the faceless, confidential documents chronicle the intimate details of a mental health crisis that has devastated families, overwhelmed the health care system and pushed countless New Jerseyans to the brink. He writes of people’s deepest secrets and lowest moments.

So many are going through the same experiences, he said. He wishes they didn’t feel shame.

“It’s shocking how many people are still just not sharing it with anyone,” he said. “The number of times I’ve been the first person someone shared a horrible, horrifying experience with is just unfair.”

He files the report and silently waits for the next crisis. The air conditioning hums in the background.

A few minutes later, he hears the chime again.